Between the Living and the Dead

To Trinity, And Already There

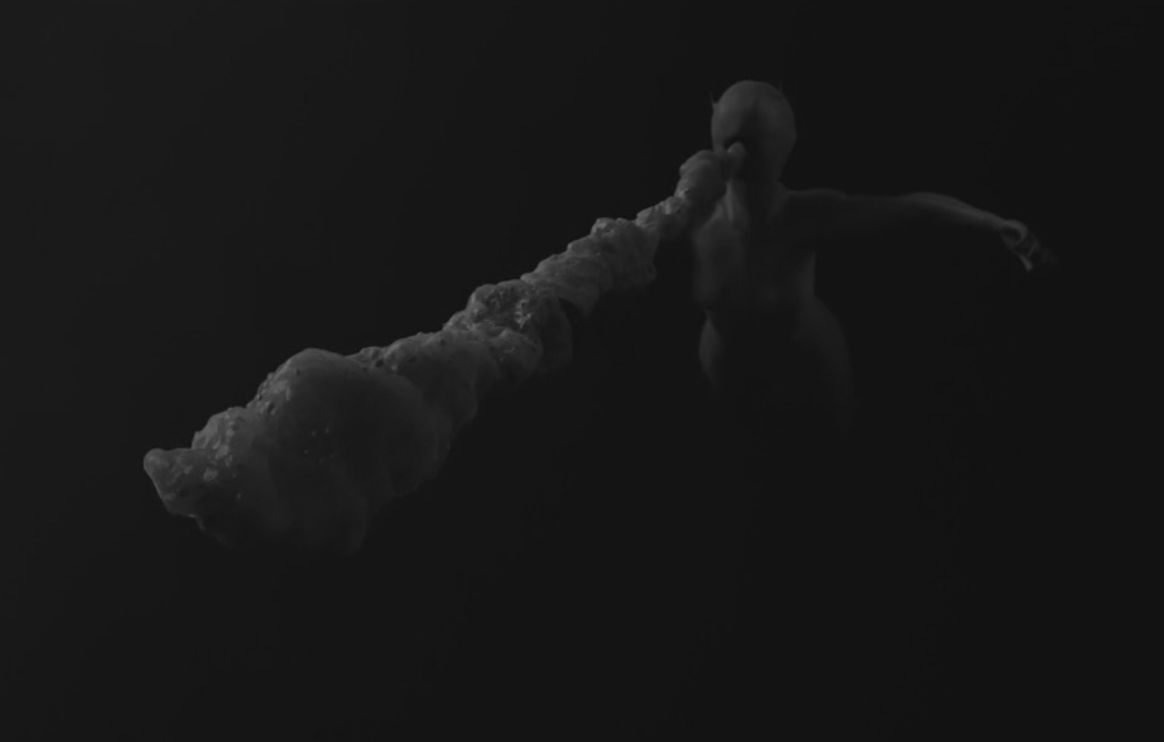

In the summer of 2017, halfway through the long-awaited return of the 90’s cult TV show Twin Peaks, creators David Lynch and Mark Frost finally offered an answer to the dreadful question that made the show so popular: who killed Laura Palmer? Although fans had learned the identity of her killer during the show’s original run, it wasn’t until twenty-five years later that Lynch and Frost located the source of the violence and cruelty that led to the death of the show’s central victim. In Episode 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return (“Gotta Light?”) we learn that, far from the Douglas firs of the town of Twin Peaks, the evil at the heart of the show’s mythology arose in White Sands, New Mexico in 1945, with the testing of the first atomic bomb at Trinity Site, which in the universe of the show literally unleashes or births new demons, ready to haunt and terrorize. From the mushroom cloud a figure emerges (Figure 1), horrible and enormous, and from her mouth a stream that culminates in the first appearance of BOB, the show’s ultimate villain. We now understand Twin Peaks to be not about solving the murder of a teenage girl, but rather contending with an evil created by humans, but far more powerful than any human alone. Drawing out the dreadful implications more explicitly, composer Krzysztof Penderecki’s dramatic elegy, “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima,” plays over the surreal imagery, reminding the viewer that the horrific potential created through this military test would soon be realized, prematurely ending hundreds of thousands of lives.

Twin Peaks atomic bomb test creature (Showtime).

Twin Peaks atomic bomb test creature (Showtime).For some, it may have seemed an unexpected origin for the world of the show, which previously had been so contained by a small town in the Northwest of the United States, visited only occasionally by FBI agents and international investors. Why this site, Trinity? Why, in 2017, this return to 1945? As I attempt to describe the event, I’m frustrated by language that seems insufficient and received—“evil unleashed,” and “horrific violence”—and appreciate again Lynch and Frost’s use of music and an almost unreadably dark and surreal imagery to depict the test that ushered in the nuclear age. To use Trinity, however, as a symbol for what we might understand to be the “root of evil” is in some ways to contain it, in spite of the show’s fractured temporality and unsettling visual vocabulary, in a familiar teleological narrative where evil is born or created and heroes rise in response, and with them the promise of resolution. How might we instead understand Trinity Site as already implicated in a history of devalued lives and land, of state-sanctioned violence and death, not as a source, but as an already entangled reverberation, neither origin nor conclusion, not an answer, but part of a question that remains open and lived?

In Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory, Lisa Yoneyama writes, “Too often those who speak of Hiroshima’s past assume its inherent and inevitable significance. Yet for many the need to know Hiroshima’s past and present is far from self-evident. How can those who see no existential link to this place, its history and people, begin to realize that their lives are inseparably interconnected with what went on and continues to go on there?” (39).The two books I turn to below—Leslie Marmon Silko’s 1977 Ceremony and Kyoko Hayashi’s 2000 From Trinity to Trinity—arrive at Trinity Site through an entangled web of such inseparable interconnection as Yoneyama describes. In both books, the central characters arrive at Trinity at climactic moments of the texts, but rather than find simple resolution, they instead locate themselves and their kin within the already, inextricably bound net between New Mexico, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, between lives and nations and worlds, between the past, the present, and the yet-to-come. I will first explore these books in depth, then look to how they allow us to push back against the logic of place as static and naturalized, against the logic of distance as measurable and contained, and against the logic of linear time with a past that can do nothing but recede further and further away into irrelevance and powerlessness. By challenging these formative, normative logics, we can imagine other ways of valuing and learning, and so other ways of living and imagining.

FROM TRINITY TO TRINITY

In From Trinity to Trinity, Kyoko Hayashi, herself a hibakusha, a survivor of the atomic blast in Nagasaki, makes a pilgrimage to Trinity Site in the year 2000, at the end of the twentieth century. As hibakusha, she is forever connected to the bomb in body and memory, the traces of the bomb embedded within her, in some ways herself a trace. Early in the book she recalls that when she explained her plans for this trip, her friend Rui asked if she’s “an atomic bomb maniac” and she answered, “Maybe, I said with a wry smile. But the truth is, even today I still want to break away from August 9. One morning I awoke to find my saliva was pink, because during my sleep I had some bleeding in my gums. On these occasions I have always wished I was not related to August 9” (9). Later, from a hotel in Albuquerque, Hayashi writes to that same friend, “When I told you I was coming to Trinity, you asked me if I was an atomic bomb maniac. I wonder with what I can possibly fill the fifty-two schoolmates in my grade. I want to embrace the emptied spaces but my hand reaches towards nothing” (33). As a hibakusha storyteller she feels a responsibility to her fifty-two lost schoolmates; her sense of responsibility is both personal and exceeds her; her relationship to the event, its consequences for her own life, and the lost lives of her schoolmates remains a complex and mobile web that she both carries and is carried by.

On her way to Trinity Site, she and another friend, Tsukiko, who has lived in the United States for many years, visit the National Atomic Museum, where mushroom cloud T-shirts and Fat Man pins are sold in a souvenir shop. The only other visitors are white people, mostly men, who glance at maps of Japan and impassively watch documentaries about the bombings. For Hayashi, the visit overwhelms her. “I felt time stop in front of the panel” (16), she writes, and later, “I had wholeheartedly believed that nuclear disarmament represented humanity’s conscience. The old man’s eyes shattered that myth. The men, listening to the old man’s comments, were perhaps feeling love for their country. The elderly man looked older than I, so he must have fought in the 1940s. The glorious past the Atomic Museum illustrates is what his generation fought for” (20). The patriotic American nationalism Hayashi perceives in these men, this pride in the bomb and certainty of its necessity, is not uncommon in the narrativization of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the United States. Such violence must somehow be justified in the memories of its perpetrators, in the stories that they tell. The bomb here is not the “root of evil,” but the beginning of peace, its horrible condition of possibility.

Hayashi and Tsukiko leave the museum. The last stop on their journey is Trinity Site, Ground Zero, which is open to visitors just twice a year, on the first Saturdays of April and of October. She looks for signs of life in the desert, but the only movement comes from the walking of the other visitors. She writes:

From the bottom of the ground, from the exposed red faces of faraway mountains, from the brown wasteland, the waves of silence came lapping and made me shudder. How hot it must have been —

Until now as I stand at <Trinity Site,> I have thought it was we humans who were the first atomic bomb victims of Earth. I was wrong. Here are my senior hibakusha. They are here but cannot cry or yell.

Tears filled my eyes.

I have always been aware of being a hibakusha. But as soon as I started walking through the small passage within the fenced area led by a guide, my always-present awareness of being a victim disappeared from my mind. It was as if I became a fourteen-year-old again. I may have been walking toward an unknown < Ground Zero > as though I were someone from < the time > before August 9, but it was when I stood in front of the memorial that I was truly exposed to the atomic bomb. (50)

In experiencing viscerally her connection with this damaged land, Hayashi finds neither peace nor resolution, but instead new kin, or rather a new recognition for kin that has always been with her, but previously unsensed. The consequences of the bomb do not begin and end with humans, indeed do not begin and end at all. This land was colonized and robbed, the uranium stolen from Indigenous people, just as the test site was stolen, just as the nation was stolen.

Near the exit, which is also the entrance, Hayashi watches an officer use a Geiger counter to demonstrate the remaining radiation in an alarm clock that was used in the test explosion, and the visitors watch in awe as the detector rings. Hayashi writes, “Realizing how ridiculous it is for me to be among them, I felt like I wanted to put that Geiger counter on my body as a demonstration. When it starts to ring Gaaaaaaaaaa they would be surprised, I thought” (53). As Hayashi reflects on the more-than-human consequences of the bomb, these other visitors seem to forget or neglect the consequences of humans entirely. In their essay “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering,” Karen Barad considers radiation exposure and its quantification as a reduction of human bodies to units of measurement: “Used by the postwar Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission to set standards for radiation exposure, hibakusha bodies have been reduced by U.S. officials to a yardstick for measuring bodily tolerance limits, although they have proven inadequate; in actuality, these figures are more a measure of entangled capitalist-imperialist-racist forms of violence and exploitation” (106).

The book ends with another message to Rui. Hayashi writes, “The world does not need your experiment.—Rui, what do you think?” (57). With Rui, we too are asked what we think of this experiment’s necessity, of the nature of its critical role not only to the past, but to the present and the future.

CEREMONY

Leslie Marmon-Silko’s Ceremony tells the story of a young Laguna Pueblo man, Tayo, returning home from his service in World War II. His experience of violence, both enacting and surviving it, his time as a Japanese prisoner of war, and the death of his cousin, Rocky, with whom and for whom he enlisted, has left him deeply sick. His time in white military hospitals offered no healing from his post-traumatic stress disorder, and he spends most of the first half of the book shivering and vomiting in bed, or drinking and fighting with his friends and fellow veterans. He is invisible and empty. Despite concerns from his aunt, who fears the judgment of her neighbors and feels ashamed of Tayo’s sickness just as she feels shamed by any failure to thrive under the violence of colonialism, his grandmother sends for a local medicine man, Ku’oosh. After meeting Tayo, Ku’oosh connects him with another medicine man, Old Betonie, a Navajo living in Gallup, and through this connection links Tayo’s suffering to a much longer narrative of violence and healing that cannot be contained within the framework of one discrete life and death, or even within one family or clan across generations, or one history of one world. In these meetings the ceremony begins, and Tayo must find a way to complete it in order to temporarily halt the evils of the witchery that began not only with the war, but also with all colonial enterprising and destruction. This ceremony leads finally to Trinity Site, and from there to an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life and death, living and dying, to a recognition of the connection between the devaluing of Indigenous life and the devaluing of Japanese life, and to glimpsing what more can be possible when this entangled web is uncovered. Ku’oosh clarifies that the ceremony is not for Tayo alone, far from it, it is for this fragile world. Silko writes:

The word he chose ‘fragile’ was filled with the intricacies of a continuing process, and with a strength inherent in spider webs woven across paths through sand hills where early in the morning the sun becomes entangled in each filament of web. It took a long time to explain the fragility and intricacy because no word exists alone, and the reason for choosing each word had to be explained with a story about why it must be said this certain way. That was the responsibility that went with being human, old Ku’oosh said, the story behind each word must be told so there could be no mistake in the meaning of what had been said; and this demanded great patience and love. (35)

The ceremony Ku’oosh is proposing requires Tayo (and with him the reader) not to enter into this web, because he is (and we are) already entangled, already constituted by the web, but rather it requires Tayo to embrace his location in the web, to accept responsibility for telling its story, protecting its fragility, its gorgeous intricate entanglement.

This entanglement is most visible at Trinity Site to which Tayo unintentionally flees, persuaded by white military doctors who seek to capture and incarcerate him in a military hospital, thinking him insane and dangerous. Once he realizes where he has wound up, he knows he has reached the end of the ceremony:

There was no end to it; it knew no boundaries; and he had arrived at the point of convergence where the fate of all living things, and even the earth, had been laid. From the jungles of his dreaming he recognized why the Japanese voices has merged with the Laguna voices, with Josiah’s voice and Rocky’s voice; the lines of cultures and worlds were drawn in flat dark lines on fine light sand, converging in the middle of witchery’s final ceremonial sand painting. From that time on, human beings were one clan again, united by the fate the destroyers had planned for all of them, for all living things; united by a circle of death that devoured people in cities twelve thousand miles away, victims who had never known these mesas, who had never seen the delicate colors of the rocks which boiled up their slaughter…

He cried the relief he felt at finally seeing the pattern, the way all the stories fit together—the old stories, the war stories, their stories—to become the story that was still being told. He was not crazy; he had never been crazy. He had only seen and heard the world as it always was: no boundaries, only transitions through all distance and time. (246)

Not an origin, neither end nor beginning, for Tayo, Trinity Site is a convergence, where the separations manufactured to maintain colonial and national violence fail. Like Hayashi, Tayo is brought to tears by this revelation, not from the relief of finding some type of peace or satisfactory answers, but from the feeling, the recognition of the vastness of this interconnection. All that is left for him to complete this ceremony is to make it through the night, to survive, and though it is a night marked by formidable terror, he does.

I turn now from my close readings of these texts, to explore how these works guide us toward thinking differently about the logic of static, confined and confining place, the logic of distance that measures through proximity and visibility, and the logic of linear, teleological time. All of these logics maintain the discrete separability of events and locations in a way that effectively occludes their profound, constitutive interconnection; the intricate, fragile web within which nothing exists self-contained isolation.

LOGIC OF PLACE

As bombs are made, as towns are made, as armies are made, so too are places made—purposefully, with particular intentions to create and foster some possibilities while foreclosing upon others. The more the intentionality and design behind a place can be hidden by the appearance of inevitability or natural-ness, the more effectively and insidiously will those possibilities develop or wither as intended. As Katherine McKittrick explains in Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, “Geography’s discursive attachment to stasis and physicality, the idea that space ‘just is,’ and that space and place are merely containers for human complexities and social relations, is terribly seductive: that which ‘just is’ not only anchors our selfhood and feet to the ground, it seemingly calibrates and normalizes where, and therefore who, we are” (xi). According to this trained understanding, place is flat and immovable, itself fundamentally unchanging even as human events transpire and human lives change upon it. There is a permanence to place, grounded, landlocked, destined to be nothing but what it “just is.” McKittrick goes on to explore the consequences of static, inevitable place and space for the people who make their lives in any particular location and are therefore understood as somehow statically and inevitability identified with that place, bound to it, writing, “This naturalization of ‘difference’ is, in part, bolstered by the ideological weight of transparent space, the idea that space ‘just is,’ and the illusion that the external world is readily knowable and not in need of evaluation, and that what we see is true” (xv).

There is no necessary problem in being bound to a place, to the land. To feel connected to where you are from and where you live, to feel that it is part of who you are and something for which you can and will be held responsible, by your neighbors and your broader community—human and non-human alike, both those present and those who came before and those who are yet to come—is an entirely different kind of place-making than the kind McKittrick describes. This place-making isn’t about inevitability, but relationships and responsibility. In an examination of sacred sites and the impossibility of measuring and so containing their spiritual meaning, the Ojibwe scholar and activist Winona LaDuke writes:

Since the beginning of times, the Creator and Mother Earth have given our peoples places to learn the teachings that will allow us to continue and reaffirm our responsibilities and ways on the lands from which we have come. Indigenous peoples are place-based societies, and at the center of those places are the most sacred of our sites, where we reaffirm our relationships.

Everywhere there are Indigenous people, there are sacred sites, there are ways of knowing, there are relationships. The people, the rivers, the mountains, the lakes, the animals, and the fish are all related. In recent years, US courts have challenged our ability to be in those places, and indeed to protect them. In may cases we are asked to quantify “how sacred it is, or how often it is sacred.” Baffling concepts in the spiritual realm. Yet we do not relent, we are not capable of becoming subsumed. (66)

As described by LaDuke, place, though ancient, is far from static and unchanging. Place is not exclusively constituted by human use or activity, but rather through relationships with and between humans, animals, bodies of water, geologic formations, and everything that makes its lifeways together on the land.

In both Ceremony and From Trinity to Trinity, it is when the central characters realize the depth of their relation to the land, to the place that is Trinity Site, that as they are constituted by that relationship, so too is Trinity Site constituted, that new possibilities open up for going on, for living after and healing from the violence and trauma of World War II. This does not mean moving on with a clean break, or finally closing a chapter, but rather coming to feel and understand that what was meant to be closed off and contained, as by the fence around Trinity Site, can never be so, as a relationship is never a closed circuit, but an extensive network that reaches out and makes contact, that constitutes the place and the people it touches.

LOGIC OF DISTANCE

With this touching, we also come to push back against the logic of distance, where connection can only be measured through proximity, in presence or absence. LaDuke addresses this in the previous quote with the challenge it presents to simple quantification—where and when is a site sacred, and how far does this sacred site reach, what is the radius of the sacred site? To be touched by a location doesn’t necessarily mean to be geographically contiguous or proximate to it, as Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not “close to” Trinity Site in miles, but nevertheless are connected to it by an unbreakable touch.

The logic of distance, like the logic of place, is meant to contain, to draw borders and divisions, to foreclose upon the possibility or realization of connection. The logic of distance works to obscure that connection, because with it comes the possibility of coalition. As Thuy Linh Nguyen Tu writes in The Beautiful Generation: Asian Americans and the Cultural Economy of Fashion:

As American political discourse of red states and blue states attests, we continue to find it difficult to imagine ourselves as interconnected and our fates as intertwined. This is not just a problem of difference, for even as official multiculturalism has made social differences more palatable, it has not fundamentally challenged the divisions between us and them.

This presumption of distance and disconnection has had the effect of obscuring the circuits that have always linked together culture and labor, material and immaterial, here and there, and a host of other domains imagined as distinct. It has made it even more difficult to see proximity, contact, and affiliation, and to conceive of the conditions under which coalitions might thrive. (206)

Distancing operates in how we work, how we live, how we make our homes, how we understand who we are and where we belong, what belonging even means. Distancing instructs us to believe that if something or someone is “far away” then it must be irrelevant; it cannot possibly be part of who and what we are. To be distant from is to be disconnected from, untouched and unmoved by. This logic is particularly relevant and damaging for a place like Trinity Site—a place of stolen land and stolen resources that are then used to devalue and decimate certain lives and certain ways of living.

Relevant to all of this discussion is the reality of environmental racism, where certain areas, and certain people living in those areas, existing at a “safe distance” from other, more valued areas and people, become understood as disposable “sinks,” sacrificed to protect those other areas and people. In “Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism, and state-sanctioned violence,” Laura Pulido explains that sinks are “… places where pollution can be deposited. Sinks typically are land, air, or water, but racially devalued bodies can also function as ‘sinks’” (529). Trinity Site, like the body of Hayashi (and Tayo, in a different way, as an Indigenous army veteran), is a toxic sink, with the endlessly lingering radiation as proof and reminder of its disposability and devaluing.

But even this toxicity pushes back against the organizing logic of distance and, with distance, containability. In her essay “The Enactment of Intention and Exception through Poisoned Corpses and Toxic Bodies,” Teena Gabrielson explains that, “With visceral, affective force, toxic substances subvert traditional binaries such as nature/culture, violate the integrity of longstanding categories like the human body and its environment, and traffic in the social, political, material, technological, scientific, and discursive” (173). Distance alone cannot protect anyone from toxicity, as toxins travel across boundaries and time, implicating the whole world in their spread. It is a capitalist fantasy that some areas can be sacrificed so that others might thrive. The borders meant to contain, the distance meant to control, are only imagined as excuses not to disrupt the continued functioning of industry. As Pulido explains, “Indeed, the state is deeply invested in not solving the environmental racism gap because it would be too costly and disruptive to industry, the larger political system, and the state itself” (529). To protect industry and the state, the entire world is contaminated, while still pretending that contamination exists only at a distance. While of course it is the case that the experience of that contamination is still unevenly distributed by design, nevertheless its consequences implicate us all. There is no truly “safe distance.” Having never been allowed this fantasy of safe distance, already sinks themselves, Tayo and Hayashi nevertheless dismantle the logic of distance when, upon arriving at Trinity Site, they both realize that in many crucial ways they were already there, had always already been there, touched by the site ages before stepping foot inside the fence.

Pushing back against the logic of distance means also pushing back against the logic of visibility, the logic that promises that if you cannot see something, it is not there, it does not matter, it is so irrelevant as to be practically unreal, the logic that tells us that only visible presence is presence. Against this reliance on the visible, we must learn to feel our way into relation with not only what is present, but what is meaningfully absent, what has been lost to and in time.

LOGIC OF LINEAR TIME

If time is a straight line moving mercilessly forward, then the past can do nothing but fall further behind, memory can do nothing but recede deeper and deeper into a safe distance, and can never touch us again, as we are indexically chained to this moment alone, this moment the only one that matters, the only one that is material.

The radioactivity of Trinity Site, and the memory-work and storytelling in both Ceremony and From Trinity to Trinity tell us otherwise. The land is haunted, as are both Tayo and Hayashi. Haunting is not an abstract metaphor, but full, active, and in a sense, alive. Again from “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering,” Karen Barad writes, examining the quantum indeterminacy of both time and space:

Hauntings, then, are not mere rememberings of a past (assumed to be) left behind (in actuality) but rather the dynamism of ontological indeterminacy of time-being/being-time in its materiality. And injustices need not await some future remedy, because ‘now’ is always already thick with possibilities disruptive of mere presence. Each moment is thickly threaded through with all other moments, each a holographic condensation of specific diffraction patterns created by a plethora of virtual wanderings, alternative histories of what is/might yet be/ have been. Re-membering, then, is not merely subjective, a fleeting flash of a past event in the inner workings of an individual human brain; rather, it is a constitutive part of the field of spacetimemattering. (113)

These hauntings that follow or guide Tayo and Hayashi to Trinity Site challenge the certainty and determinacy of absence and loss as permanent, as ontologically, materially gone, lost forever. As Barad writes “When it comes to nuclear landscape, loss may not be visibly discernible, but it is not intangible… Loss is not absence but a marked presence, or rather a marking that troubles the divide between absence and presence” (106), or as Fred Moten writes in Black and Blur, “Disappearance is not absence” (viii), again pushing against the visible and apparent as the only present, both in time and in space.

Remembering is a material activity, an engagement with absence, with time as shifting, brimming with possibilities. In no way does this erase the violence, or return to the fullness of living to those dead and disappeared, but rather it pushes against their continued erasure from the consuming narrative of “here and now.” Even in acknowledging and feeling the presence of who and what has been lost, their absence is underscored as well, all the more keenly. As Lisa Yoneyama writes in Hiroshima Traces, “… the very task of speaking as proxy for the dead already marks the latter’s silence. The survivors’ narrative practice, as a trace, reminds us of the absence of what is presented, certifying that the dead and the surviving will never again share the same temporality” (142).

Though one sense of temporality can never again be shared between the living and the dead, the work of remembering and storytelling nevertheless calls forth and points to a meaningful, constitutive relationship between the living and the dead, and a continued responsibility to the dead, for all that has been lost, out of respect not only for the memory of the dead, but also to protect the living and the not-yet-born. As Yoneyama explains:

To be effectual, the witness’s testimony must be heard as resonating across time: the audience must be able to imagine the story about the past as a possible future event. The ‘never again’ aphorism is therefore predicated on a dialectics of memory—a constant movement between memory constituted by the authenticity that derives from the witness’s capacity to tell what actually happened and memory cast into the future. (134)

The work of storytelling, as demonstrated by Hayashi in telling not only her own story, but the absence of stories for her schoolmates, and by Silko through the fictional story of Tayo and his relatives, moves through this dialectical memory—what happened, what might have happened, what will happen, what might happen.

This way of remembering and memorializing contrasts sharply with the permanent solidity of the Trinity Site Obelisk. The obelisk has two plaques. The first reads: “Trinity Site / Where The World's First Nuclear Device Was Exploded On July 16, 1945 / Erected 1965 White Sands Missile Range J. Frederick Thorlin Major General U.S. Army Commanding.” And the second reads: “Trinity Site has been designated a National Historical Landmark / This Site Possesses National Significance In Commemorating The History of the United States of America / 1975 National Park Service United States Department of the Interior.”

Pointing to the same massive sky from which two atomic bombs have been dropped, nothing could feel more immovable, more unrepentant in its conveyed certainty, inevitability, than the flat declaration that “This Site Possesses National Significance In Commemorating The History of the United States of America,” as if all the land’s significance begins and ends within the borders of the United States and its history, tightly contained. Predicated on static place, measurable distance, and linear time, the obelisk seems to promise or demand containment and confinement, but all around it, the expansive, haunted desert landscape tells another story, or indeed tells many other, interconnected, intricate, fragile stories—what happened, what might have happened, what will happen, what might happen. The remembered and the imagined far from identical, but crucially not unrelated.

++++++

In this paper I have sought to explore how Hayashi and Silko use memory and storytelling to challenge containment and confinement, to illuminate connection and entanglement. In no way is that entanglement a way to flatten or universalize experiences of harm and suffering, or to bring about a tidy resolution to a history of violence and oppression and murder. Rather, entanglement challenges the possibility of resolution, neither simple question nor answer. In “Critical Refugee Studies and Native Pacific Studies,” Yến Lê Espiritu defines “critical juxtaposing” as:

… the bringing together of seemingly different and disconnected events, communities, histories, and spaces to illuminate what would otherwise not be visible about the contours, contents, and afterlives of war and empire. While the traditional comparative approach conceptualizes the groups, events, and places to be compared as already constituted and discrete entities, the critical juxtaposing method posits that they are fluid rather than static and need to be understood in relation to each other and in the context of a flexible field of political discourses. (486)

I have explored how these characters and places described by Silko and Hayashi don’t evolve—as in, work towards an end—but rather shift and change in constitutive relation across time and space.

Moving against a logic that organizes through division, categorization, and containment, I have attempted to explore this place, Trinity Site, through constitutive relationships, through dialectical memory, with an ear to the ground and eye out for absence. What can be contained can be controlled, made into an official narrative, a site on a map surrounded by a fence, opened to the public twice a year, but otherwise remote and inaccessible. Constitutive relationships across time and space, across “type” of being—human, non-human, present, absent, living, non-living, dead—cannot be contained, or perhaps only insofar as they are themselves the container that has room enough for everything. Already bound together in this entanglement, what else is there but to be responsible and accountable to everything in the web, not only as memorial, not only to ensure a “never again” to nuclear destruction, not only for a hoped for future, but because we are already responsible, we are already interconnected, we are already there, it is already happening right now, in this place and this moment, wherever it may be, entangled and replete.

Notes

Back to Between the Living and the Dead

Copyright © 2020 Laura Henriksen